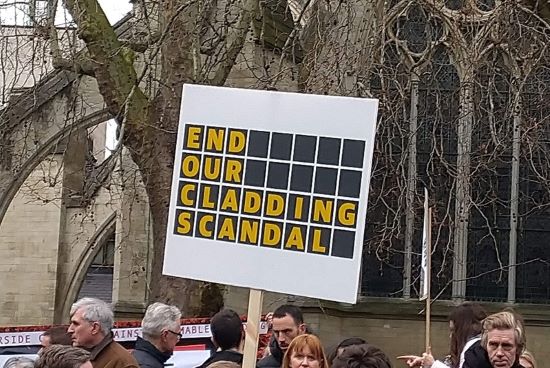

The ongoing cladding crisis means that tens of thousands of UK households are living under a cloud of uncertainty about the safety of their own homes. In this long read, Clare B Marshall considers some possible solutions to address a complex situation.

Recognised as a fundamental human right by the UN and embodied in human rights law around the globe, is the right to adequate housing - to live somewhere that is secure, sustainable, adequate and safe. More recently, the UN is again leading the charge through its sustainable development goals (SDGs), including goal 11 - to make our cities and communities inclusive, resilient, sustainable - and safe.

Four years since the devastating Grenfell tragedy, the bereaved and survivors continue to await the outcome of the Inquiry into the causes of the fire and of future proceedings to establish accountability. More widely, thousands of UK households live under a cloud of uncertainty as to the adequacy and safety of their own homes and the timeframes within which they will be made safe.

The Surfside building partial collapse and subsequent demolition in the US and the Morandi bridge tragedy in Italy are other disasters providing a stark and shocking reminder of the roles, responsibilities and accountability associated with the procurement, design, build and long-term maintenance of buildings and structures.

Fundamentally, who will bear the cost of remediation and recompense to the bereaved, survivors and wider community directly impacted, remains a complex and open issue. I do not seek to comment here on the investigations, inquiries or the civil claims the survivors and bereaved families have already underway, nor on the potential for prosecutions and sanctions.

As to the thousands of other households and families who live in impacted buildings - such as in the UK with high-risk cladding materials or other fire safety risks - it is painful to read reports of the stress created by the situation. Stress, not only for those in most need of help with the remediation of their homes, but stress arising from an existential crisis impacting colleagues across all sectors of the built environment.

And this is stress which has significant personal, physical and mental impacts, extending further into various realms of business and wider market conditions. We see this on both the design and build side of the equation and, most notably, in the insurance market.

Wider impact of the crisis

The availability of insurance has swung from a position of full coverage for cladding, fire safety and fire performance in buildings, to highly reduced coverage. In the current 2021-22 insurance renewal season we see further restrictions and, in some cases, no cover at all. This is a direct response to the proliferation of cladding-related legal claims. Hundreds of millions of pounds tied up and vast sums invested in legal processes and associated costs.

So, as legal wrangles increase, more time, money and energy is spent pointing fingers, adding a heightened risk of many firms going bust in the meantime. The critical time available to fix the problem is being lost to legal wrangles resulting in further delays to the remediation of existing buildings and prolonged stress for their residents. And funds, which could be better used to find solutions, fix the problem and address the real issue - the right to adequate housing - are lost.

We can also imagine the consequence of no (or very limited) insurance for many highly skilled architects, engineers, designers, contractors, specialist fire consultants and other critical advisors. That is, either the withdrawal of their specialist skills and experience completely (for fear of uninsured future liabilities) or a very cautious and narrow approach to their project work, stifling thoughtful and intelligent innovation and creativity.

Critically, the skills needed to deal with the replacement of cladding and address other fire safety issues may become unavailable or limited seeing a depletion of skills and resource and a deterioration in buildings. Buildings which need to be fit for other challenges, including the many risks presented by climate change.

I am biting my fingers, seeking to avoid commenting on the politics of the current situation in the UK. Following significant public pressure, the government soon moved on from its immediate response in the aftermath of the Grenfell tragedy, where it placed the onus on property owners to fix the problem.

Progress? Yes, with new legislation in the pipeline and wider consultations on funding on the horizon. But the current measures are not moving fast enough nor going far enough. The draft legislation does not yet include critical detail around funding urgently needed to remediate high risk buildings. Indeed, the government continues to press for leaseholders themselves to contribute to repairs to their buildings.

More needs to be done - and fast. So, what are the solutions?

Fixing the problem

For the answer look in part to Australia and in particular to the work initiated by the Victorian Cladding Taskforce following the fire in the 23-storey Lacrosse residential tower in Melbourne in 2014.

The taskforce, chaired by John Thwaites and Ted Bailleau (who came from either side of the political spectrum and who each had a background in the industry), moved at pace and its work and recommendations focussed around four key elements - audit, rectification, funding and future facing (a new approach to construction methods, selection of building materials and regulation).

The model has since been adopted across Australia and with funding from central government contributing to the costs of cladding removal. A cladding levy has also been in force since last year and should see a contribution to at least half the costs of remediation.

The success of the scheme was directly attributable to the team maintaining a clear focus on their first responsibility - the safety and wellbeing of the residents of the buildings. Every decision made would be judged against essential criteria - providing the most protection, to the most people, in the shortest time.

A complex and painful problem which would take years to solve if the team became lost and confused in the complexity and vested interests. The mission was simplified through a clear, and defendable, focus. It was this focus that supported the government funding decision, with the levy on building permits and the direct involvement of government in building rectification.

Job done? Well, nearly.

Funding relies, in part, on financial recovery from developers, contractors and design teams of the affected building. The state government has step-in rights to fund litigation and pursue those responsible. Important issues of liability to be resolved through the justice system, currently running its course. But the focus was on the safety and wellbeing of residents and solving the problem first.

Back to the UK, it is highly important that those who (through gross negligence, deliberate acts, fraud or other serious failings) have caused the problem are held to account through the justice system.

But there is another category of stakeholders here - the many in the industry who have found themselves caught up in a problem not of their making and now face lengthy and challenging litigation. A reliance on the courts and lengthy legal wrangles will take years to conclude and could see many in the industry running out of assets, with very limited insurance available to meet their liabilities. Again, creating more uncertainty.

The question of cause and accountability is a complex one and must not delay or take attention away from the immediate issue of remediating unsafe homes.

Finding a funding solution

Funding is the critical issue at the heart of this crisis. In the UK the cost of remediation is estimated to be in the region of £15bn. To date the UK government has announced a contribution of £5bn.

Akin to the funding scheme in Australia, at the time of writing, the UK Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government has just launched a consultation on the Building Safety Levy which is open for feedback until October 2021. The levy could well be in line to sit alongside a new tax on developers which has already been the subject of consultation and is now into design development.

A Building Safety Fund (which should in fact be a building ‘performance’ fund to capture all issues that will likely be encountered by homeowners) has also been established. Yet feedback from the legal sector indicates that the application form does not specify how far a claimant needs to take their action against the alleged wrongdoer. It merely requires a box to be ticked confirming legal action has started. This has led to letters of claim (under pre-action protocols) being issued as a protective measure with few claimants taking actual proceedings, rather requesting a standstill. It seems housing corporations, homeowners’ associations and other impacted parties are all waiting to see what happens in parliament.

So, we have a complex web of funding options and issues and a moving feast at the time of writing. It is a complex and challenging situation overall, requiring a package of measures. And, as in Australia, a focus on people and safety first.

Fundamentally, the proposed measures do not fully address the immediate and urgent issue of how remediation schemes are taken forward with haste. Nor do they address the risk, to all involved or impacted, of the very little insurance available for future projects and the consequential risk of a shrinking skill base.

So, I would dare to add an element, requiring government intervention and a collective and collaborative approach (in addition to a sensible approach to levies and tax regimes). A scheme led and funded up-front by government, without contribution from leaseholders and residents, with a contribution from all key stakeholders in the built environment, including insurers, from funds already set aside and available.

The scheme should include special government-funded indemnities to specialist advisors and contractors whose skills are critical to seeing through effective remediation works. Instead of the supply chain pointing fingers and fighting each other through the courts for years to come, this additional and unnecessary time, cost, energy (and associated stress) can be avoided.

By bringing real focus to the urgent task of remediating unsafe buildings - through a collective effort and by pooling existing funds and reserves - work can start immediately, alongside investment in skills, improved technical standards, assurance and innovation for future projects.

Government and parliament must intervene, bring that focus and provide the necessary funding to fix this problem. This is all fundamental to achieving the desired outcome, which is securing buildings which give residents their right to adequate housing and a safe place to live.

Clare B Marshall is the founder of the business consultancy 2MPy.