Consistently ranked at the top of healthy city indexes, Copenhagen is a world leader when it comes to scores of happiness, mental health and activity levels but as London strives to play catch up, are its aims ambitious enough to inspire serious change?

The difference between the two cities is plain to see. With five times as many bikes as there are cars and its streets connected by approximately 300 miles of “super bikeways” - dedicated specifically for two-wheelers - it’s little wonder that Copenhagen is highly-decorated when it comes to attaining healthy city status.

London’s challenge is no doubt a much more daunting one with it at least 10 times bigger than the Scandinavian city but in its attempts to find itself on a level footing, questions on how committed the government and the mayor of London is to make the city a greener, sustainable and happier place to live continue to mount.

John Haxworth, a partner and head of the Landscape Design Team at the planning and design consultancy Barton Willmore, says convenience is always key. “If it’s quicker, easier and cheaper then whatever your environmental point of view, you’re going to support it,” Haxworth claims. “If you provide the right type of infrastructure, people will use it.”

But how has Copenhagen become the leader it is when it comes to attaining healthy city goals? Haxworth who has recently visited the Danish capital on a study trip, believes the real triumph is how high-level infrastructure has been delivered to all levels of the city and not just a series of high-profile, high-cost major interventions that don’t filter down to everyone.

“It’s the all-pervasive provision of infrastructure on all scales that comes down to the individual city blocks and the creation of a culture that nudges people into going out into open green spaces by increasing the rate of walking or cycling,” the Barton Wilmore partner claims. “People in Copenhagen haven’t suddenly decided to use greener forms of transport because they believe its morally right, it’s because it’s the easiest and quickest way of getting to work or the kids to school.”

Keeping people active is also a central theme in Copenhagen’s healthy journey. The 2017 Annual Bicycle Report revealed how cycling is king for inhabitants with 62% choosing to bike to work or school/college. In total, 1.4million km is cycled in the city on an average weekday which was recorded as an increase of 22% since 2006.

A proposed cycle superhighway proposed for Hammersmith, west London.

But despite efforts in London to pick up the pace for cycling infrastructure with the development of cycle superhighways, what has the Danish capital been able to achieve that its European competitors haven’t?

“At the moment the infrastructure we are putting in place within London like the cycle superhighways is quite a lumpy approach,” Haxworth said. “It’s a large piece of infrastructure that has met some resistance and is only ever used by men in lycra, you don’t get lots of mums and dads taking kids to school or people using them from one block to another. There is not that cultural acceptance that cycling is the right thing to do. It comes down in part to the infrastructure not yet in place across the city with lots of areas still unconnected.”

The issue of air quality is another vital component that cities around the world need to consider if they are to match targets set by the World Health Organisation.

Next month (8 April) marks another pivotal moment for London with Sadiq Khan poised to introduce London’s Ultra Low Emissions Zone. It means that every vehicle entering the congestion charge zone will have to pay £12.50 if it does not meet basic emission standards and will be in addition to the congestion charge.

"To say we need to keep central roads in London open to buses is a bit ludicrous. It's about taking a brave step and not just always looking at the challenges."

Lucy Wood, Barton Willmore.

Lucy Wood, an environmental and planning director at Barton Willmore, is part of the London team and is very interested in air quality within the capital.

She believes decision-makers within London “still need to take the bull by the horns” when it comes to environment challenges. “This is a real issue and it’s not only killing people but we are missing out on an opportunity of huge investment,” Wood explains. “If the UK was driving industry towards better technology and cleaner ways of living then economic benefits would also ensue.”

Wood thinks the “jury is still out” when it comes to how feasible it is for the UK to achieve targets set out in its clean air strategy which aims to cut air pollution and save lives, backed up through primary legislation and believes the government’s track record does not fill many with confidence.

She said: “If you look at things like carbon reduction and air quality in the past we have failed to meet EU target levels time and time again. I’m always a little frustrated that timescales aren’t set sooner, for example, the clean air strategy aims to stop producing conventional petrol and diesel cars by 2040 and for me that’s just not soon enough.”

A controversial idea in some circles, the environmental expert would like to see the mayor and council leaders look once again at closing central London roads like Oxford Street to all vehicles - something Copenhagen did in its central district more than 30 years ago despite the initial backlash from shopkeepers.

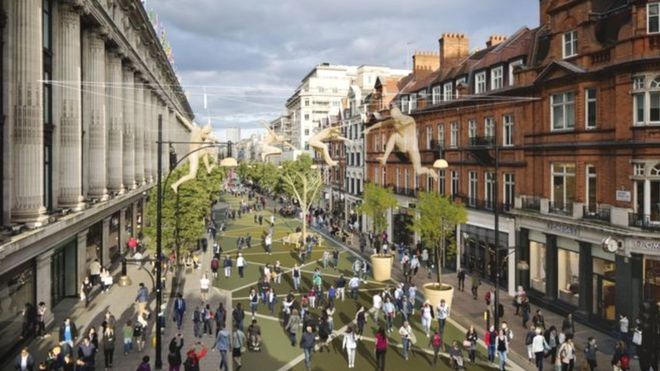

What a pedestrianised Oxford Street in London could look like.

Wood said: “If you close Regent Street or Oxford Street to traffic then you potentially have quite a wide piece of green infrastructure. This then brings a community effect with lots of pop-up stalls and play areas. To say we need to keep some central roads open to buses is a bit ludicrous when it would be quicker to walk. It’s about taking a brave step and not just always looking at challenges but also the opportunities.”

But while top-down approaches filtered down from the powers that be are important in building hard infrastructure, the Barton Willmore team members agree that this is not enough on its own to see change.

Haxworth added: “What we are finding is that you can provide all the infrastructure but without a shift in culture, changing the mindset of people and bringing everyone with you then it’s difficult for a city or a country to achieve real health gains.”